Clause

1. What is a Clause?

A clause is a set of words containing a subject and a predicate. Every full sentence has at least one clause—it is not possible to have a complete sentence without one. Sometimes, a clause is only two words, but it can be more. Because of this, it is the shortest way you can express a complete thought in English!

It’s easy to remember what a clause is—just use this simple “word equation”:

2. Examples of Clauses

In the examples, subjects are purple and predicates are green. As mentioned, some clauses are only two words, a subject and a single verb predicate, like these:

- I see.

- He ran.

- We ate.

- They sang.

Other times, instead of a single verb, a predicate can be a verb phrase, so a clause can be longer, like these:

- I see you.

- He ran away.

- We ate popcorn.

- They sang beautifully.

3. Parts of a Clause

All clauses have two main things, a subject and a predicate.

a. Subject

A subject is the person, place, idea, or thing that a sentence is about. It’s the noun that is “doing” something in the sentence. Every sentence needs at least one to make sense. Sometimes a subject is only one word, but sometimes it includes modifiers, or can be a noun phrase or gerund.

b. Predicate

A predicate contains a sentence’s action—it tells what the subject does, and always needs a verb. Often the predicate is just a verb, but it can also be a verb phrase: a verb plus its objects or modifiers. Here are three examples of different types of predicates in clause:

- The dog ran. Single verb “ran” = predicate

- The dog ran quickly. Verb + modifier “ran quickly” = predicate

- The dog ran home. Verb + object “ran home” = predicate

4. Types of Clauses

There are two main types of clauses that we use in sentences. They are called independent clauses and dependent (or subordinate) clauses, and each works differently in a sentence and on its own.

a. Independent Clause

An independent clause is a clause that is as a complete sentence. Basically, it’s just a simple sentence. Like all clauses, it has a subject and a predicate, and makes sense on its own.

- The dog ate popcorn.

- He ate popcorn.

- The dog ate.

- He ate at the fair.

You can see that each sentence above is complete; you don’t need to add any other words for it to express a complete thought.

b. Dependent (Subordinate) Clause

A dependent clause has a subject and a predicate; BUT, unlike an independent clause, it can’t exist as a sentence. It doesn’t make sense on its own because it doesn’t share a complete thought. A dependent clause only gives extra information, and is “dependent” on other words to make a full sentence. Here are a few examples:

- After he went to the fair What did he do after?

- Since he ate popcorn Since he ate popcorn, what?

- While he was at the county fair What happened?

- If the dog eats popcorn Then what?

Though all of the examples above contain subjects and clauses, none of them make sense on their own. So, dependent clauses are very important, but they need independent clauses to make a full sentence, which make complex sentences. Alone, a dependent clause makes a fragment sentence (see Section V).

Furthermore, there are several types of dependent clauses, like noun clauses, adjective (relative) clauses, and adverb clauses. In the sentences below, the clauses are underlined.

i. Noun Clause

A noun clause is a group of words that acts as a noun in a sentence. They begin with relative pronouns like “how,” “which,” “who,” or “what,” combined with a subject and predicate. For example:

The dog can eat what he wants.

Here, “what he wants” stands as a noun for what the dog can eat. It’s a clause because it has a subject (he) and a predicate (wants).

ii. Adjective (Relative) Clause

Adjective clauses are groups of words that act as an adjective in a sentence. They have a pronoun (who, that, which) or an adverb (what, where, why) and a verb; or, a pronoun or an adverb that serves as subject and a verb. Here are some examples:

The dog will eat whichever flavor of popcorn you have

Whichever (pronoun) + flavor (subject) + have (verb) is an adjective clause that describes the popcorn. As you can see, it’s not a full sentence.

The dog is the one who ate the popcorn.

“Who” (pronoun acting as subject) + “ate” (verb) is an adjective clause that describes the dog.

iii. Adverb Clause

An adverb clause is a group of words that work as an adverb in a sentence, answering questions asking “where?”, “when,” “how?” and “why?” They begin with a subordinate conjunction.

The dog ran until he got to the county fair.

This sentence answers the question “how long did the dog run?” with the adverb clause “until he got to the county fair.”

After the dog arrived he ate popcorn.

With the adverb clause “after the dog arrived,” this sentence answers, “when did the dog eat popcorn?”

REMEMBER: NO TYPE OF DEPENDENT CLAUSE CAN BE A SENTENCE BY ITSELF!

5. How to Avoid Mistakes

There are a couple of common mistakes that can happen when using clauses. First, you need to remember rules about subject-verb agreement. Second, it’s important to avoid fragment sentences. And of course, always remember: CLAUSE = SUBJECT + PREDICATE!

a. Subject-Verb Agreement

Each sentence has a subject and a verb, but as you know, subjects and verbs both have singular and plural forms. In order for them to function properly, they need to “agree” with each other, or match, which is called subject-verb agreement (SVA). Clauses rely on subject-verb agreement to make sense. Look at these two sentences:

The dog likes popcorn. Correct SVA

The dog like popcorn. Incorrect SVA

The dogs like popcorn. Correct SVA

The dogs likes popcorn. Incorrect SVA

Now, here are some key rules to remember:

- Singular subjects need singular verbs

- Plural subjects need plural verbs

- A mix of singular and plural results in subject-verb disagreement.

- Sometimes single and plural verbs are the same

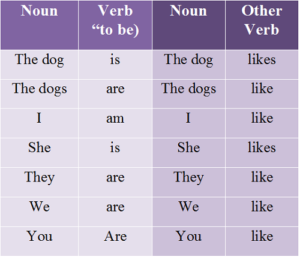

You probably already know the difference between singular nouns and verbs and plural nouns and verbs. Here’s a chart to help you remember some:

b. Fragment Sentence

A “fragment” is a small piece of something. So, a fragment sentence is just a piece of a sentence: it is missing a subject, a predicate, or an independent clause. It’s simply an incomplete sentence. As mentioned, using a dependent clause on its own makes a fragment sentence because it doesn’t express a complete thought.

Let’s use the dependent clauses from above:

- After he went to the fair What did he do after?

- Since he ate popcorn Since he ate popcorn, what?

- While he was at the county fair What happened?

- If he eats popcorn Then what?

As you can see, each leaves an unanswered question. So, let’s complete the sentences them:

- The dog was tired after he went to the fair.

- Since he ate popcorn, the dog didn’t want dinner.

- While he was at the county fair, the dog ate popcorn.

- The dog will get a stomachache if he eats popcorn.

Here, the independent clauses are underlined. In each of the sentences above, the dependent clause is paired with an independent clause to make it complete. So, always remember: a dependent clause needs an independent clause!